(This article is the basis for Episode 7 of the BotaCast. Due to the nature of this episode, I wanted to experiment with a video version of the podcast, find it on my YouTube channel here)

The bad news is that if you use in-ear monitors, I guarantee you have experienced a bad mix. Loud, but you can’t seem to hear anything. Something is off with the pitch and it feels like vocalists notes are going flat. The good news is that you can radically improve your mix with a few adjustments, and (probably) without having to spend any money.

If your monitor mix sucks, more drivers in your headphones might not fix your problems. Investing thousands of dollars into a new monitor hardware or software might be an expensive, time consuming distraction that doesn’t change any of your frustrations. Maybe it is time to make some gear changes, but before you spend any money, you might find an infinitely better mix by adjusting how you build your mix.

Building a monitor mix can be counterintuitive. Back when in-ear monitors (IEMs) were limited to large scale setups that had monitor engineers, you had someone who could pop into different people’s mixes, diagnose problems, and help make strategic changes to your levels, EQs, FX, etc. But when Avioms and other personal mixers came on the scene, worship teams members were just thrown into building their own monitor mixes. With a little bit of training, you can help yourself and your team have consistently better sound. So today, we are leveling up your in-ear monitor mix.

Spy On Your Worship Team(’s Mixes)

I have a confession to make: I snoop on my teams’ in-ear mixes. This all started back when my worship team switched from avioms to iPad controlled monitor console mixes. After rehearsals, I would lock up our iPads and I began to look at what people’s mixes looked like. Especially those who seemed to have a difficult time at rehearsal: whether it was pitch, rhythm, or general frustration with their in ear experience. This was fascinating to me, and I have never stopped. To this day, if a team member is struggling with their performance, one of the first things I do is investigate their mix. Based on what I’ve seen, here are five big mistakes and bad habits I see when it comes to building an in ear mix.

- Vocal Mic Overload

If you’re a vocalist, you probably have your vocal mic too loud. Beyond a bad mix, this can quickly cause massive pitch issues. I have seen (or rather, heard) this mistake cripple the pitch of even great vocalists.

The reason: the Doppler effect. If it’s been a while since high school physics, the Doppler effect is what you experience when you hear a train’s horn passing by. The pitch seems to slide lower as the distance between you and the passing train increases.

Here’s what happens for vocalists: when you start singing, you are on key. Then, the PA carries your voice to the side and back walls of the room. The sound bounces off the wall, and then comes back to the stage, but because of physics the notes come back a little flat. This wouldn’t be too big of a problem, except that your microphone is turned up in your ears so loud that this reflection now becomes your tonal reference. When you hear those notes a little flat, your ear says “Oh, I’m sharp!” and then you start singing flat. As you can imagine, this spirals pretty quickly as the next reflection comes back even more flat, you sing even more flat, and on it goes until there’s a measure when you’re not singing and your ear can orient back to something consistent like piano.

This is exacerbated if your team builds their monitor mix while the PA is muted. Because there are no reflections, you won’t notice this effect until things get rocking in the room.

This also compounds if all the vocalists have themselves and each other up too loud. The whole vocal team will then collectively go flat since “I need to really hear what everyone else is singing, but I definitely need to hear myself the most!”

So the big question is: Where should your personal vocal mic level be? It should be loud enough to comfortably hear yourself, but just below what you think would be the ideal point. The sweet spot is where you wish you had just a little more.

- “A Little Bit of Everything”

The temptation is that you’ll have a “full mix” with all the channels turned up. But the truth is that you’ll just have a “cluttered mix.” What’s worse is that you’ll probably also have a loud mix as you have trouble picking out what you need to hear above the jumble of all the other inputs. This is especially true if you happen to have the misfortune of a mono mix (no panning left/right, no stereo separation).

The best mixes are strategic and spartan. If you want a great blend of everything together, you should go listen to the recording or enjoy the FOH mix from the seats. Your in-ear mix should have only what you need, and nothing that you don’t.

Unless your the drummer, I guarantee you don’t need any hi-hat or cymbals in your mix. If you’re on bass, you don’t need to hear the BGV—even if you’re married to her. Nobody needs the choir in their in-ears. Ever.

When a worship team member asks for help with their mix, subtraction is the first step. Unless the channel is essential to rhythm, pitch, or determining what you’ll be playing on your instrument: start with it off, add back in slowly to taste.

"The temptation is that you’ll have a full mix with all the channels turned up. But the truth is that you’ll just have a cluttered mix."- Daniel Tsubota Click To TweetIf you have a mono mix, your “budget” when it comes to what makes it into the mix is even smaller.

You’ll also be amazed at the amount of things you’ll be able to hear just through vocal or talkback mic bleed, crowd mics, or just from the PA/room itself even with noise isolating earbuds.

- No Headroom

This is when the individual channels are turned up high, but the master volume is turned down low. This is the most technical (read: boring) mistake, but it has the power to make the biggest change right away in your mix.

(I’m going to discuss the problem and solution below, but it will probably easier to see/hear what I’m talking about in the video version of this article here.)

Here’s the scenario: you’re at rehearsal. Everything seems to be fine when people are going one by one checking their instruments. But once everything is really cranking together, suddenly it becomes hard to hear much of anything. It doesn’t make any sense because you have everything turned up pretty loud, the level in your ears is definitely loud, and you can hear yourself very distinctly when the song is over and you play something solo.

This compression is caused by high channel output and too low master volume.

Imagine this: each of the channels in your mix is a water spigot with a garden hose attached to it. You have 32 of these garden hoses all being fed to one PVC pipe at the end. This pipe represents the master volume of your mix: let’s say the volume knob of your wireless pack. What would happen if you had all the spigots turned on nearly all the way, but the PVC pipe that receives all the hoses is only a half inch wide. It would be a really squeezed mix of all the garden hoses. If you turned off all the spigots but one (let’s call that one your guitar), the water from that garden hose would flow smoothly through the PVC pipe as you would hope.

This is what happens when your master volume is too low.

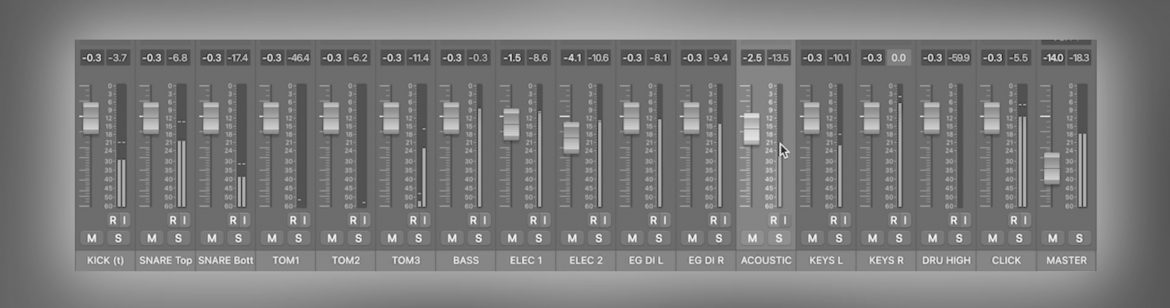

(The video version of this podcast shows individual channel meters that are all pushing audio signal nicely, but the low master channel headroom is causing major squashing when all the inputs are going. When just one input is solo’d, it seems fine because there is headroom for that one channel, but as channels start getting added back in, the collective mix is squashed to fit the low output limit)

Now imagine that the PVC pipe is 12” wide. Now all of the water from the garden hoses can flow well, and there can even be some dynamics during those moments when only 4 or 5 of the spigots are on.

The solution: start with your master volume much higher than you have before. If your pack has been at 3, try starting with your master at 5 or 6. Your faders will all have to be much lower than you’ve had them: probably all within the 0-50% range. I typically find that I have my pack volume at a good place when my loudest channels are right at 50%.

Now you might be wondering: if a higher pack volume is better, why not just set the master to 10? The danger of going too high is that you lose precision in your volume adjustment. The difference between channel volume increment “dots” would start going from silent to blow-off-your-face with the tiniest volume change. If you want to learn everything about gain structure, head on over to my friends at https://getmxu.com

- Making Adjustments Before Getting Adjusted

If you rehearse during the week, it can seem like a gremlin came in and ruined your mix when you come back on Sunday. If you liked talking about physics in #1, get ready because it’s time for some physiology! There are so many differences in your body and environment from a Thursday night rehearsal to a Sunday morning soundcheck: the time of day, how awake you are, when your last meal was, what you ate, the heating/air conditioning in the room, morning vs evening humidity, and on and on. All of this will change how you perceive your in ear mix.

The good news is that your ears will adjust. Just like your eyes adjust when you walk from a dark backstage hallway out into the blinding noon sun. You don’t have to turn the sun down: give it a minute and things will even out. Your ears are just as good at making the necessary adjustments even if your mix sounds a little funky when you first get soundcheck going on Sunday morning.

What can happen is you start making adjustments to your good Thursday mix, and then once your ears “warm up,” your new mix sounds worse than when you started making changes! My rule of thumb is that unless something is so dramatically bad that you can’t focus (e.g. the click seems to have doubled in volume, or you can’t hear MD talkback), leave the mix alone and see if your ears adjust.

"Constant mix changes is a distraction for you as a musician."- Daniel Tsubota Click To TweetMaking adjustments can also be problematic to the rest of your team. What can happen is that as musicians stop playing to make mix changes, the other band members think, “Hmmm… I can’t hear guitar, let me turn that up…” then the keys player says, “Did I lose bass guitar? I’ll just make a quick change…” then the guitarist wonders where keys went, you get the idea. This cycle just continues as the band members come back in only to blow away the people who had turned up their channel while they weren’t playing. Let’s not even get started on the cuss words your audio engineer is stringing together at front of house while all this is going on.

Constant mix changes is a distraction for you as a musician. I once played with a keys player who had one hand on the Nord and the other on the Aviom. The. Entire. Set.

Band: you don’t need to adjust the vocalists song by song. Keep them all low, I guarantee you will hear the lead just fine when it’s their turn to let loose.

- Not using EQ or Compression

If you haven’t been utilizing any dynamic adjustment in your monitor mix, it’s time to start. Your drums will come to life with the right compression, and you’ll be thrilled to have vocal reverb in your ears. Using onboard effects is much better than trying to use crowd mics as your reverb (see mistake #1 for how physics can make things problematic). Even something as simple as high pass filters on channels can clean up the low end of everyone’s monitor mix.

For too long, monitor signal has just been the afterthought of whatever could be slopped into the wedges or Aviom channel. Times have changed though—for the better, much better. If your current system doesn’t offer any EQ, dynamics, or FX, there are so many great consoles that can be used to run monitors (Yamaha TF, Behringer X32 come to mind – both have rack mount versions) and provide IEMs with all the royal treatment that used to be reserved for FOH.

If you’re not happy with your monitor mix, you do not have to live with constant frustration. There are many free adjustments that could liberate the quality of your mix. As worship teams, we spend hours preparing what you play. Our audio teams pour (hopefully) a lot of effort into the sound of just one weekend. It’s worth the time and energy to invest into the in-ear sound that your team uses every single service. Once you become experienced in building and troubleshooting your in-ear mix, you’ll be so thankful to be rid of those frustrations. Leveling up your monitors is an essential foundation for your worship team’s next steps of development.

Catch this month’s BotaCast for an even deeper dive into this topic.